Still unclear on how HB 5902 affects Illinois advisers, students? This Q&A will help!

SPLC’s Frank LoMonte comes to the rescue with practical guide on Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act

Note: This information is courtesy of Frank LoMonte of the Student Press Law Center. If you have additional questions, please contact the SPLC through their legal request site, by email, or call (202) 785-5450.

Illinois House Bill 5902, The Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act: What It Means To You

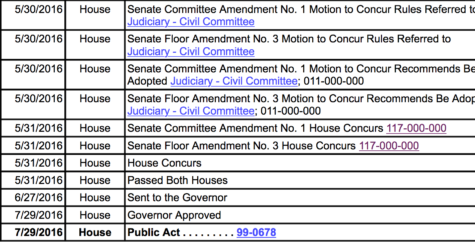

On July 29, 2016, Gov. Bruce Rauner signed HB 5902, the Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act, into law after the bill received the unanimous approval of the Illinois House and Senate. With the governor’s approval, Illinois became the ninth state in the country with a statute giving high school journalists heightened protection against school censorship above-and-beyond the protection provided by federal law (on Oct. 1, 2016, Maryland became the tenth state).

HB 5902 was part of a nationwide initiative, New Voices (New Voices Facebook), with the goal of neutralizing the impact of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1988 ruling, Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, which diminished the First Amendment rights of students speaking in the context of a class-produced, curricular medium. The purpose of the law is to improve young people’s civic readiness by giving them the ability to speak without fear about issues of social and political concern in journalistic publications, including issues involving policies and events at their own schools.

To whom does HB 5902 apply?

The Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act protects students in public high schools, including charter schools, in Illinois. Student journalists at public colleges and universities already had comparable protection by way of the College Campus Press Act, 110 ILCS 13/5 et seq., enacted in 2007.

The law protects students working under the guidance of a faculty adviser on media in any format (print, online or broadcast) that is made available to a student audience, other than material prepared as an academic assignment for presentation exclusively within the classroom. Students already had this level of freedom in publications that they produce independently with their own resources, as a result of the Supreme Court’s 1969 ruling in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District,[1] which applies to non-curricular forms of expression.

Note that the right to be protected against censorship applies, by statute, to “the appropriate student journalist” responsible for each publication. This was an effort to clarify that every student does not have a legally enforceable right to have his or her speech accepted for publication; for example, the law could not be invoked to compel a student editor to publish every column submitted by every would-be student author.

Does HB 5902 give students press freedom equivalent to that of professionals?

No. HB 5902 enumerates limited grounds on which schools may remove or alter the content of student-produced media, effectively restoring the level of student editorial discretion that existed before the Hazelwood decision. A school is forbidden from engaging in the “prior restraint” of student expression unless the school can meet the burden of demonstration that the expression fits one of four unprotected categories enumerated in the statute: (1) the speech is libelous, slanderous, or obscene; (2) the speech constitutes an unwarranted invasion of privacy; the speech (3) violates federal or state law; or (4) the speech incites students to commit an unlawful act, to violate policies of the school district, or to materially and substantially disrupt the orderly operation of the school.

Note that the terms “libelous,” “slanderous,” “obscene” and “unwarranted invasion of privacy” are well-defined terms in the law of the First Amendment, and HB 5902 is to be read in conjunction with that established body of legal precedent. In particular, speech may not be restrained as “libelous” or “slanderous” merely because it is critical of individuals or institutions or because it exposes unflattering information; “libel” and “slander” require proof of a false statement of fact. Also note that the statute refers to “unwarranted” invasion of personal privacy, which is understood to mean that certain private facts are of public interest and concern and therefore are fair game to be published.

How will HB 5902 work in practice?

Let’s take several hypothetical examples of speech that might be submitted to a student publication:

EXAMPLE 1: A student reporter prepares an article based on a police report in which a classmate has been charged with manslaughter for a fatal drunk-driving crash. Crimes and information derived from police reports are, by definition, matters of public interest and concern, and a truthful article about criminal charges against a student based on information gleaned from public records may not be withheld. There is no invasion of privacy in publishing the contents of a police report involving a matter of public concern, even when the subject of the report is under 18.

EXAMPLE 2: A student editorial writer denounces the superintendent’s new scheduling policies as “moronic” and calls for the school board to fire the superintendent. Phrases of opinion are, by definition, not capable of being libelous or slanderous; HB 5902 would protect the editors’ right to publish the editorial.

EXAMPLE 3: A student journalist submits a column that consists of gossip and rumors about the sexual habits of named classmates. The sexual practices of private citizens are of no public concern or importance, and the column could lawfully be withheld on the grounds of invasion of privacy.

How can a state law “overrule” a Supreme Court decision?

This is a common misconception. When the Supreme Court decided Hazelwood, it was setting the floor beneath which states could not go. It was not setting a ceiling.

To illustrate: If the Supreme Court says that confining inmates in a cell smaller than 60 square feet constitutes cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment, that does not mean that states are required to provide exactly 60 square feet and no more. When the Court rules on questions of individual constitutional rights, as in Hazelwood, the Court is establishing how far a state may choose to go in regulating its citizens – not how far a state must go. Laws such as HB 5902 have been applied in court six times nationally,[2] and on no occasion has any judge found any constitutional problem with a state granting students more than the bare minimum of rights than the Constitution requires.

An appellate court in Iowa dealt with the interaction of Hazelwood and state law in the 2011 case of Lange v. Diercks.[3] In that case, a high school journalism adviser was disciplined for failing to stop students from disseminating a humor edition of their newspaper containing jokes about steroid use, bribery and other topics that the principal deemed inappropriate for a teen audience. The Iowa Court of Appeals vacated the discipline and ordered the teacher’s clean record restored, finding that the teacher’s authority to restrain the publication of lawful and non-disruptive speech was limited by an Iowa statute that is the functional equivalent of Illinois HB 5902.

The judges explained that the statute, Iowa Code § 280.22, was enacted “for the purpose of giving students more robust free-expression rights than those articulated by the Supreme Court” and that the statute “prohibits school officials from exercising prior restraint of student publications to the extent allowed under Hazelwood.”[4]

There is a misperception that the Hazelwood Court granted school administrators a “right” to censor that states cannot take away. That is not the way rights work. Rights protect individuals (students) against the government (schools), not the other way around.

Hazelwood remains on the books as far as the federal courts are concerned, but a student in Illinois who is unlawfully censored now has the ability to bring a claim in state court to enforce state-protected rights.

What speech does HB 5902 protect that isn’t protected today?

When students are censored by schools, the most common justification they report being given is “making the school look bad.” Image-based censorship is now unlawful in Illinois. Mere damage to a school’s reputation does not constitute a “substantial disruption” to school functions or activities. An article may not be restrained or rewritten, or its authors or editors punished, on the grounds that it portrays the school in an unfavorable light. Students are permitted to voice complaints about their schools or bring to light the dissatisfaction of others.

Can’t a school suppress controversial or critical speech by labeling it “disruptive?”

“Substantial disruption” does not mean merely speech that causes controversy or provokes strong differences of opinion. By way of example, federal courts in the federal Seventh Circuit, which includes Illinois, have found the following expression to be non-disruptive and therefore protected against school censorship by the Tinker standard: (1) wearing a shirt bearing a Marine Corps slogan accompanied by a photograph of a rifle,[5] (2) wearing apparel with slogans expressing opposition to homosexuality,[6] and (3) disseminating a video containing mild sexual humor on an off-campus social media account.[7] On each occasion, the speech provoked complaints from offended viewers, but in each instance, the courts found the speech to be legally protected and beyond the school’s authority to proscribe.

Courts in the Seventh Circuit have found the following speech to be substantially disruptive, and therefore subject to being proscribed under the Tinker standard that is codified in HB 5902: (1) publishing detailed instructions about how to hack into school computers,[8] (2) walking out of class as part of a protest,[9] and (3) drawing gang symbols on school assignments on multiple occasions.[10]

As can be seen from these illustrative cases, speech is substantially disruptive if it realistically threatens the safety of the school, portending that the student will engage in unlawful behavior or will incite others to do so. Speech is not substantially disruptive just because it offends some audience members or touches on sensitive subjects. Further, the forecast of disruption must be based on factual experience and not speculation. As then-Circuit Judge Alito wrote in a 2001 ruling, “Tinker requires a specific and significant fear of disruption, not just some remote apprehension of disturbance.”[11] HB 5902 thus provides a meaningful check on school censorship authority, and “disruption” may not be lightly invoked to suppress controversy or criticism.

A helpfully explanatory case is the Seventh Circuit’s 1970 opinion in Scoville v. Board of Education, [12] a case decided on the basis of the Tinker level of school authority that now applies to school-sponsored media.

In the Scoville case, three students were expelled for disseminating a self-produced newsletter they created in rebuttal to a pamphlet sent home to parents that described the school’s disciplinary rules in ways that the students found ridiculous. The publication contained a variety of statements deemed objectionable by administrators, including urging students to throw away future pamphlets distributed by the school, denouncing the protocol for obtaining a waiver to excuse an absence as “utterly idiotic and asinine,” and stating that a dean’s quote in the pamphlet extolling the virtues of discipline was “the product of a sick mind.” Nevertheless, the Seventh Circuit judges found the speech to be protected and beyond the school’s authority to discipline. Merely exhibiting a “disrespectful and tasteless attitude toward authority” did not support a realistic forecast of substantial disruption, the judges ruled. This level of protection is now applicable to all student-produced media made available to a student audience, whether as part of a journalism course or entirely self-published.

What does the law mean for advisers?

HB 5902 does nothing to interfere with the authority of a teacher to teach best journalistic standards and practices, including making and grading classroom assignments. Those practices are unaffected by the law. However, advisers are school employees, and therefore may not use their authority to rewrite or remove an article for reasons forbidden by the statute. Specifically, an article may not be withheld from publication on the grounds that it will provoke controversy or complaints.

As was recognized in the Iowa Court of Appeals’ aforementioned Lange ruling, a school employee may not be disciplined for failing to engage in behavior that violates state law. To illustrate, a teacher could not lawfully be fired, demoted or reassigned for refusing an unlawful instruction to racially segregate the students in her classroom. Similarly, a teacher may not lawfully be subjected to adverse personnel action for refusing to violate the censorship protections of HB 5902.

CONCLUSION

HB 5902, the Speech Rights of Student Journalists Act, imposes significant and legally enforceable constraints on what school administrators may remove or revise in student-produced media. Censorship that is based on concerns for image or public relations is prohibited, as is any retaliatory act against a student – or, by extension, a journalism adviser – that is meant to punish or deter legally protected expression.

See the full text of HB 5902 here.

[1] 393 U.S. 502 (1969). See also Scoville v. Bd. of Educ., 425 F.2d 10 (7th Cir. 1970), an Illinois ruling applying the Tinker standard to an independently produced student newsletter.

[2] See Tyler Buller, The State Response to Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, 66 Me. L. Rev. 89 (2013) (describing situations in which so-called “anti-Hazelwood” statutes have arisen in litigation).

[3] 2011 Iowa App. LEXIS 1251 (Nov. 9, 2011).

[4] Id. at *16.

[5] Griggs v. Fort Wayne Sch. Bd., 359 F. Supp. 2d 731 (N.D. Ind. 2005).

[6] Nuxoll v. Indian Prairie Sch. Dist. #204, 523 F.3d 668 (7th Cir. 2008).

[7] T.V. v. Smith-Green Cmty. Sch. Corp., 807 F. Supp. 2d 767 (N.D. Ind. 2011).

[8] Boucher v. School Bd., 134 F.3d 821 (7th Cir. 1998).

[9] Dodd v. Rambis, 535 F. Supp. 23 (S.D. Ind. 1981).

[10] Kelly v. Bd. of Educ., 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 68425 (N.D. Ill. Sept. 22, 2006).

[11] Saxe v. State College Area Sch. Dist., 240 F.3d 200, 211 (3d Cir. 2001).

[12] 425 F.2d 10 (7th Cir. 1970).